The Ketogenic Diet Reverses Indicators of Heart Disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide

[1]. Because of its prevalence and life-threatening nature, and because it appears that a keto diet is likely to reverse it, we consider it one of the most important conditions to discuss here.

In our last post, we argued that CVD, being a disease strongly associated with metabolic syndrome, is likely to be best treated with a ketogenic diet. In this post we will present more evidence that ketogenic diets do improve heart disease risk factors.

Unfortunately, there is much confusion and misinformation about the impact of nutrition on CVD among scientists and non-scientists alike. Not only does a high fat, keto diet not worsen heart disease risk — as would commonly be assumed — it actually improves it. This confusion about dietary fat is probably the reason that we do not yet have clinical trials directly testing the effects of ketogenic diets on CVD outcomes.

However, we already have many trials of ketogenic diets that measured known CVD risk factors, especially cholesterol profiles. It turns out that these trials show a powerful heart disease risk reduction in those following a ketogenic diet. It is powerful both in absolute terms, and in comparison with low-fat diets, which tend to improve some weakly predictive factors while worsening stronger predictors.

As such, a high-fat ketogenic diet is currently the best known non-drug intervention for heart disease, as defined by mainstream measures of risk. It is arguably better than drug interventions, too.

In brief:

- Total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol are only weak predictors of CVD.

- Triglycerides, HDL, LDL particle size, and the HDL-to-triglyceride ratio are much stronger predictors of CVD.

- Keto diets improve triglyceride levels, HDL, and LDL particle size — precisely those measures that strongly indicate risk.

Total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol are only weakly associated with CVD

The connection between blood cholesterol levels and the development of heart disease began to be explored in the last century. Over the last several decades, our understanding of the predictive power of various blood lipids has gone through many refinements as our ability to measure finer and finer detail has advanced.

In the early years, it appeared that high levels of total cholesterol carried some risk of heart disease in many cases. However, it is now well established that total cholesterol by itself is a weak predictor [2, 3, 4].

The reason is quite simple. The different subtypes of cholesterol work together in an intricately balanced system. There is a wide range of total cholesterol levels that are perfectly healthy, so long as the proportions of the subtypes are healthy ones. By the same token, a given level of total cholesterol, even if it is perfectly normal, could be pathological when examined by subtype. Strong evidence from recent decades suggests that the best known blood lipid measures for predicting future risk of CVD are HDL, triglycerides, and related ratios (see below).

Similarly, while LDL cholesterol is probably important, it appears that it does not have good predictive power when looking at its magnitude alone [5, 6, 7, 8].

One reason for this is that like total cholesterol, LDL is not uniform. Just as we distinguish between HDL and LDL, the so-called “good” and “bad” cholesterol, LDL itself is now known to have two important subtypes with opposite risk implications. Having more large, light LDL particles (also called Pattern A), does not indicate high CVD risk, but having more small, dense particles (Pattern B) does [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Therefore high LDL by itself is not necessarily indicative of CVD.

Low HDL cholesterol is strongly associated with CVD

Having high blood levels of HDL is now widely recognized as predicting lower levels of heart disease. The proportion of total cholesterol that is HDL cholesterol is a particularly strong predictor. In 2007, a meta-analysis was published in the Lancet that examined information from 61 prospective observational studies, consisting of almost 900,000 adults. Information about HDL was available for about 150,000 of them, among whom there were 5000 vascular deaths. According to the authors, “the ratio of total to HDL cholesterol is a substantially more informative predictor of IHD mortality than are total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, or non-HDL cholesterol.” [14]

This is consistent with many other studies, for example this very recent analysis from the COURAGE trial [15].

High triglycerides are strongly associated with CVD

There has been drawn out controversy in the medical community as to the relationship of triglyceride levels to CVD. There are two parts to the controversy: whether or not triglycerides are an independent predictor of CVD, and whether or not triglycerides play a causative role in CVD.

In both cases, however, it doesn’t matter in which way the controversy is resolved! Whether or not triglycerides independently predict CVD (and there is at least some evidence that they do), and whether or not they cause CVD, there is no controversy about whether they predict CVD. The association between triglyceride levels and CVD still holds and is strongly predictive [16, 17, 18]. In fact it is so predictive that those who argue that triglyceride levels are not an independent risk factor, call it instead a “biomarker” for CVD [19]. In other words, seeing high triglycerides is tantamount to seeing the progression of heart disease.

HDL-to-Triglycerides Ratio: compounding evidence

Triglycerides and HDL levels statistically interact. That means it is a mistake to treat one as redundant with respect to the other. If you do, you will miss the fact that the effect of one on your outcome of interest changes depending on the value of the other. Despite the fact that most heart disease researchers who study risk factors have not used methods tuned to find interactions between triglycerides and HDL, many studies have at least measured both. This has allowed others to do the appropriate analysis. When triglycerides and HDL have been examined with respect to each other, that is, when the effect of triglycerides is measured under the condition of low HDL, or when the effect of HDL is measured under the condition of high triglycerides, this combination of factors turns out to be even more indicative of CVD [20, 21, 22, 23].

One of the most interesting aspects of this finding from our perspective, is that the ratio of triglyceride levels to HDL is considered to be a surrogate marker of insulin resistance (See The Ketogenic Diet as a Treatment for Metabolic Syndrome.) In other words, the best lipid predictors of CVD are also those that indicate insulin resistance.

Ketogenic Diets improve risk factors for CVD

There is now ample evidence that a low carbohydrate, ketogenic diet improves lipid profiles, particularly with respect to the risk factors outlined above: triglycerides, HDL, and their ratio [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31].

Although a ketogenic diet typically raises LDL levels, which has been traditionally seen as a risk factor, it has also been shown to improve LDL particle size. In other words, although the absolute amount of LDL goes up, it is the “good” LDL that goes up, whereas the “bad” LDL goes down [31, 32]. This is hardly surprising, since LDL particle size is also strongly predicted by triglycerides [33, 34, 35].

Although there have not yet been intervention studies testing the effect of a ketogenic diet on the rate of actual CVD incidents (e.g. heart attacks), the evidence about lipid profiles is strong enough to make ketogenic diets more likely to reduce heart disease than any other known intervention.

Summary:

- Current medical practice uses blood lipid measurements to assess the risk of heart disease.

- Despite the continuing tradition of measuring total cholesterol and LDL, we have known for decades that triglycerides, HDL, and the ratio of the two, are much better predictors of heart disease. LDL particle size is also considered strongly predictive.

- A ketogenic diet has a very favourable impact on these risk factors, and thus should be considered the diet of choice for those at risk of CVD.

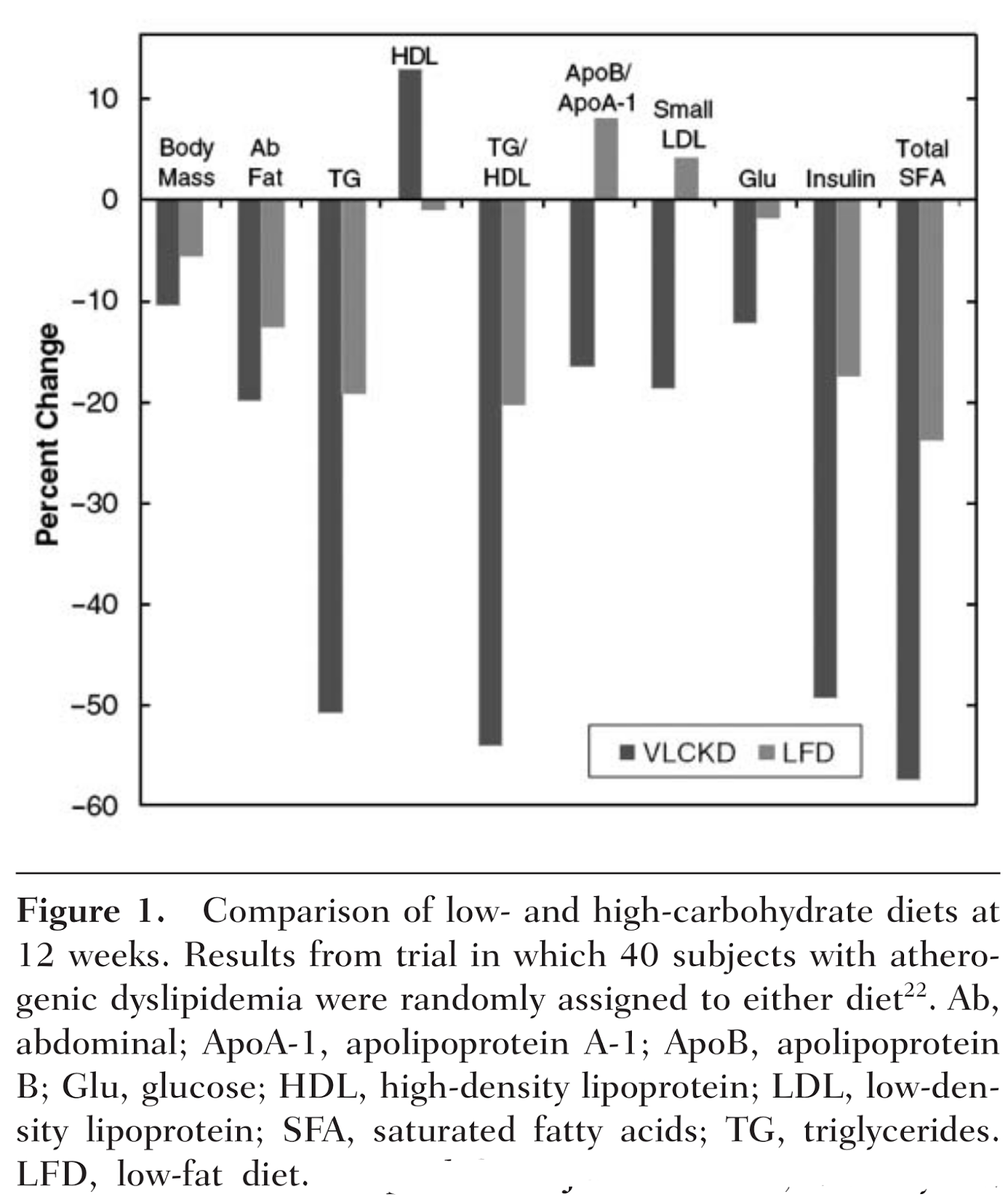

In their 2011 paper, “Low-carbohydrate diet review: shifting the paradigm”, Hite et al. display the following graph (VLCKD stands for Very Low Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diet, and LFD for Low Fat Diet) [36] based on data from [31]:

It makes an excellent visualization of the factors at stake, and how powerful a ketogenic diet is. It also shows quite clearly that not only is restricting carbohydrate more effective for this purpose than a low fat diet, but that a low fat diet is detrimental for some important risk factors — apolipoprotein ratios, LDL particle size, and HDL — but a low carb diet is not. The ketogenic diet resulted in a significant improvement in every measure.

References:

1. Evidence type: observational

World Health Organization Fact sheet N°317: Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) September 2011

- CVDs are the number one cause of death globally: more people die annually from CVDs than from any other cause.

- An estimated 17.3 million people died from CVDs in 2008, representing 30% of all global deaths. Of these deaths, an estimated 7.3 million were due to coronary heart disease and 6.2 million were due to stroke.

- Low- and middle-income countries are disproportionally affected: over 80% of CVD deaths take place in low- and middle-income countries and occur almost equally in men and women.

- By 2030, almost 23.6 million people will die from CVDs, mainly from heart disease and stroke. These are projected to remain the single leading causes of death.

2. Evidence type: observational

Role of lipid and lipoprotein profiles in risk assessment and therapy.

Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC. Am Heart J.

2003 Aug;146(2):227-33.

Despite a strong and consistent association within populations, elevated TC [(total cholesterol)] alone is not a useful test to discriminate between individuals who will have CHD [(coronary heart disease)] events and those who will not.

3. Evidence type: observational

Relation of serum lipoprotein cholesterol levels to presence and severity of angiographic coronary artery disease.

Philip A. Romm, MD, Curtis E. Green, MD, Kathleen Reagan, MD, Charles E. Rackley, MD.

The American Journal of Cardiology Volume 67, Issue 6, 1 March 1991, Pages 479–483

Most CAD [(coronary artery disease)] occurs in persons who have only mild or moderate elevations in cholesterol levels. Total cholesterol level alone is a poor predictor of CAD, particularly in older patients in whom the major lipid risk factor is the HDL cholesterol level.

4. Evidence type: observational

Lipids, risk factors and ischaemic heart disease.

Atherosclerosis. 1996 Jul;124 Suppl:S1-9.

Castelli WP.

Those individuals who had TC [(total cholesterol)] levels of 150-300 mg/dl (3.9-7.8 mmol/1) fell into the overlapping area (Fig. 1), demonstrating that 90% of the TC levels measured were useless (by themselves) for predicting risk of CHD [(coronary heart disease)] in a general population. Indeed, twice as many individuals who had a lifetime TC level of less than 200 mg/dl (5.2 mmol/1) had CHD compared with those who had a TC level greater than 300 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/l) (Fig. 1).

5. Evidence type: observational

Range of Serum Cholesterol Values in the Population Developing Coronary Artery Disease.

William B. Kannel, MD, MPH.

The American Journal of Cardiology, Volume 76, Issue 9, Supplement 1, 28 September 1995, Pages 69C–77C

The ranges of serum cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels varied widely both in the general population and in patients who had already manifested CAD (Figures 1 and 2). Because of the extensive overlap between levels, it was impossible to differentiate the patients with CAD from the control subjects.

6. Evidence type: observational

Lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoprotein A-I and B and lipoprotein (a) abnormalities in men with premature coronary artery disease.

Jacques Genest Jr., MD,FACC, Judith R. McNamara, MT, Jose M. Ordovas, PhD, Jennifer L. Jenner, BSc, Steven R. Silberman, PhD, Keaven M. Anderson, PhD, Peter W.F. Wilson, MD, Deeb N. Salem, MD, FACC, Ernst J. Schaefer, MD.

Journal of the American College of Cardiology Volume 19, Issue 4, 15 March 1992, Pages 792–802.

Our data suggest that total and LDL cholesterol may not be the best discriminants for the presence of coronary artery disease despite the strong association between elevated cholesterol and the development of coronary artery disease in cross-sectional population studies and prospective epidemiologic studies.

7. Evidence type: observational

Apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein A-I: risk indicators of coronary heart disease and targets for lipid-modifying therapy.

Walldius, G. and Jungner, I. (2004),

Journal of Internal Medicine, 255: 188–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01276.x

(Emphasis ours.)

For over three decades it has been recognized that a high level of total blood cholesterol, particularly in the form of LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), is a major risk factor for developing coronary heart disease (CHD) [1–4]. However, as more recent research has expanded our understanding of lipoprotein function and metabolism, it has become apparent that LDL-C is not the only lipoprotein species involved in atherogenesis. A considerable proportion of patients with atherosclerotic disease have levels of LDL-C and total cholesterol (TC) within the recommended range [5, 6], and some patients who achieve significant LDL-C reduction with lipid-lowering therapy still develop CHD [7].

Other lipid parameters are also associated with elevated cardiovascular risk, and it has been suggested that LDL-C and TC may not be the best discriminants for the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD) [5].

8. Evidence type: observational

Plasma Lipoprotein Levels as Predictors of Cardiovascular Death in Women.

Katherine Miller Bass, MD, MHS; Craig J. Newschaffer, MS; Michael J. Klag, MD, MPH; Trudy L. Bush, PhD, MHS.

Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(19):2209-2216.

Using a sample of 1405 women aged 50 to 69 years from the Lipid Research Clinics’ Follow-up Study, age-adjusted CVD death rates and summary relative risk (RR) estimates by categories of lipid and lipoprotein levels were calculated. Multivariate analysis was performed to provide RR estimates adjusted for other CVD risk factors.

RESULTS: Average follow-up was 14 years. High-density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels were strong predictors of CVD death in age-adjusted and multivariate analyses. Low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol levels were poorer predictors of CVD mortality. After adjustment for other CVD risk factors, HDL levels less than 1.30 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) were strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality (RR = 1.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10 to 2.75). Triglyceride levels were associated with increased CVD mortality at levels of 2.25 to 4.49 mmol/L (200 to 399 mg/dL) (RR = 1.65; 95% CI, 0.99 to 2.77) and 4.50 mmol/L (400 mg/dL) or greater (RR = 3.44; 95% CI, 1.65 to 7.20). At total cholesterol levels of 5.20 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) or greater and at all levels of LDL and triglycerides, women with HDL levels of less than 1.30 mmol/L (< 50 mg/dL) had CVD death rates that were higher than those of women with HDL levels of 1.30 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) or greater.

9. Evidence type: plausible mechanism and observational review

Particle size: the key to the atherogenic lipoprotein?

Rajman I, Maxwell S, Cramb R, Kendall M.

QJM. 1994 Dec;87(12):709-20.

Using different analytical methods, up to 12 low-density lipoprotein (LDL) subfractions can be separated. LDL particle size decreases with increasing density. Smaller, denser LDL particles seem more atherogenic than the larger, lighter particles, based on the experimental findings that smaller LDL particles are more susceptible for oxidation in vitro, have lower binding affinity for the LDL receptors and lower catabolic rate, have a higher concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids, and potentially interact more easily with proteoglycans of the arterial wall. Clinical studies have shown that a smaller LDL subfraction profile is associated with an increased risk of heart disease, even when total cholesterol level is only slightly raised. There is a strong inverse association between LDL particle size and triglyceride concentrations. Although LDL particle size is genetically determined, its phenotypic expression may also be affected by environmental factors such as drugs, diet, obesity, exercise or disease. Factors that shift the LDL subfractions profile towards larger particles may reduce the risk of heart disease.

10. Evidence type: nested case-control study

Association of Small Low-Density Lipoprotein Particles With the Incidence of Coronary Artery Disease in Men and Women.

Christopher D. Gardner, PhD; Stephen P. Fortmann, MD; Ronald M. Krauss, MD

JAMA. 1996;276(11):875-881. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03540110029028.

Incident CAD cases were identified through FCP surveillance between 1979 and 1992. Controls were matched by sex, 5-year age groups, survey time point, ethnicity, and FCP treatment condition. The sample included 124 matched pairs: 90 pairs of men and 34 pairs of women.

…

LDL size was smaller among CAD cases than controls (mean ±SD) (26.17±1.00nm vs 26.68±0.90nm;P